Abs of Steel, Soul of Dust

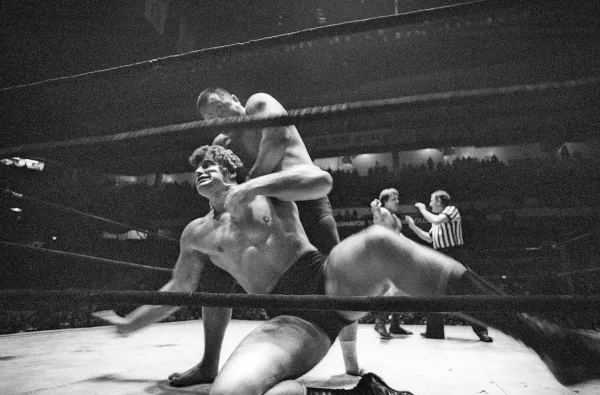

The human body has become the altar at which modern society worships, a shrine of flesh and bone draped in sweat-resistant fabrics and glowing filters. Everywhere you turn, someone is preaching the doctrine of “Wellness,” a euphemism for sculpting oneself into a socially acceptable object of admiration. Influencers hurl their chiseled physiques across social media, while the fitness industry rakes in billions by selling desperation disguised as empowerment.

We are, ostensibly, obsessed with the body — but underneath the sheen of yoga mats and kale smoothies is a deep discomfort; the quiet fear of what it means to exist. It’s a fixation that has nothing to do with the stated values of health or self-love — and everything to do with control, identity, and the unbearable truth of our mortality.

The ancient Greeks saw the body as both a vessel of divine potential and an inevitable victim of the fates. Unlike our modern obsession with perfecting the flesh as an act of defiance against death, the Greeks accepted the body’s limitations while still celebrating its beauty. They idealized physical form in their statues, yes, but not out of vanity or denial — it was an acknowledgment of the harmony between strength, intellect, and spirit.

The athlete wasn’t a shredded automaton, they were a symbol of balance, a physical manifestation of inner virtue. They didn’t try to outrun mortality by erasing their flaws or pretending decay didn’t exist.

Their gods, after all, were as flawed and doomed as they were, immortal but not infallible, beautiful but brutal. The Greeks lived with the body’s contradictions, honoring it as a reflection of human excellence while knowing that no amount of symmetry or strength would save it from the ravages of time. For them, the body was artful, yes, but never eternal — and that gave it its tragic, fleeting charm.

The body, as society frames it today, is not a vessel. It’s a product. And the production line never stops. The obsession to optimize, perfect, and render every inch of flesh shows off our need to assign value to ourselves in ways that feel…well, measurable.

If you can pinch an inch of belly fat, it’s not just a piece of you — it’s failure. If your skin isn’t smooth enough to reflect the moonlight, you’ve lost the battle against decay. We’re all competing to inhabit the “right” kind of body, but the rules change so fast it’s impossible to win. Yesterday’s Instagram grid favored the hyper-sculpted fitness model; today, it’s the carefully curated “natural” look that took six hours and a dermatologist’s paycheck to achieve. By tomorrow, we’ll all be chasing something else entirely — perhaps a new way to erase the parts of ourselves we were told not to love.

Strip away the wellness jargon and the boutique gym memberships, and what’s left?

Simple. Our hatred of the fact that our bodies are temporary.

All of this — a billion-dollar wellness industry, a million glossy magazine covers — amounts to nothing more than a scream into the void. We don’t want to face the fact that these machines of flesh and blood break down.

They ache, they sag, they wrinkle, they rot.

The body is not a temple — it’s a crumbling edifice, held together by duct tape and optimism. But the world insists we treat it as the ultimate project, something to be rebuilt, polished, and shown off until it’s time to stick it in the ground.

It’s not surprising that the glorification of the body has replaced other forms of meaning. Religion, community, and introspection have all taken a backseat to the pursuit of the perfect physique. In the absence of a deeper sense of purpose, we make idols out of ourselves.

The irony, of course, is that no amount of protein powder or cardio will stop the clock.

We obsess over our bodies not because we love them, but because we’re terrified of losing them.

We aren’t celebrating life; we’re raging against its inevitability, disguising our panic with “gains.”